Jan Bellows, DVM, DAVDC

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if you could approach dentistry without fear, anxiety, or stress? It can be done and it’s not all that difficult. Let’s dissect the touchpoints of dental fear and how to replace dread with confidence.

Client Fear

1. Fear of Anesthesia

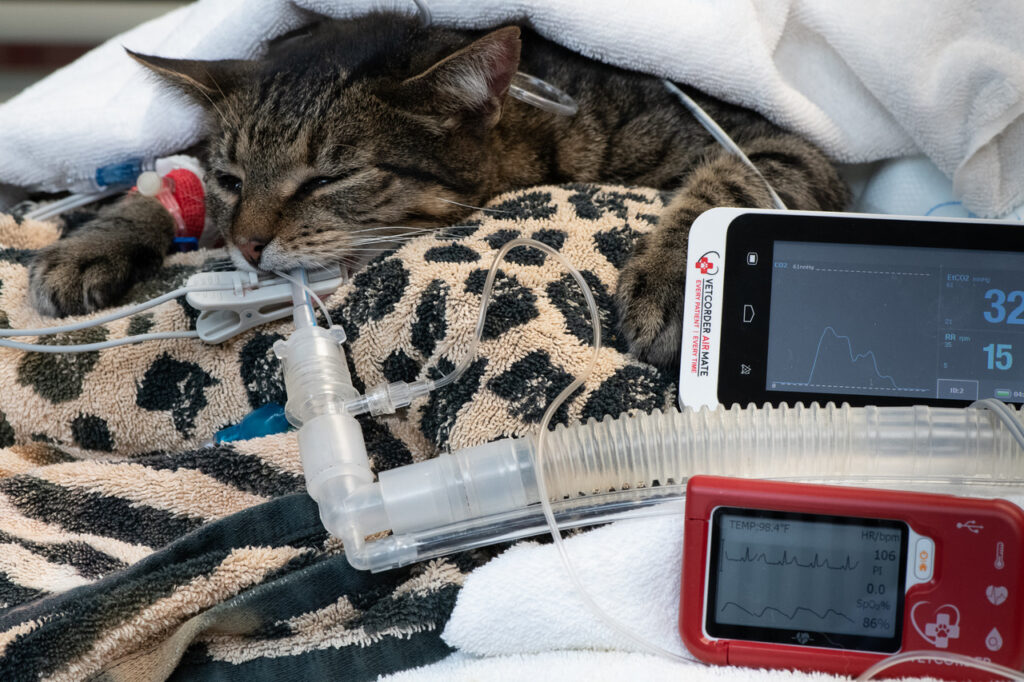

This is generally your client’s number-one trepidation. Fortunately, modern, safe anesthesia procedures include (1) evaluating the patient with physical and laboratory exam beforehand, (2) tailoring medication protocols to the patient, and (3) constant monitoring while anesthetized and during post-anesthesia recovery. Sharing these safety measures with your clients goes a long way to alleviate their fear.

2. Fear of Tooth Loss

Often clients will ask “How will my dog eat if you extract so many teeth?” The reply should be “Better than ever before because by removing the diseased teeth, the mouth will now be pain-free.”

3. Fear of Expense

This concern is often shared by both the client and veterinarian. To mitigate this fear, concentrate on what needs to be done to provide the pet with a pain-free, healthy, “happy” mouth. When asked “What is this going to cost?” early in the exam, answer that you will discuss fees “before we leave this room” and “cost is going to be part of the good news.” This can help set the client’s mind at ease and allow them to focus on their pet, the exam you’re performing, and the expertise you’re sharing. Once you’ve established an optimum treatment plan, you can work together to find the best way to make it happen, including payment.

Keep in mind that clients are used to going to their own dentist and are familiar with dental costs. Fortunately, most veterinary practices offer financing, such as the CareCredit healthcare credit card,

as a payment option. This allows clients to pay for their pet’s dental care over time in budget-friendly monthly payments rather than the entire cost upfront.

Functional vs. Optimal Care

There are bound to be challenges on the path from the basic dental care to optimum care. Most clients want to do the very best for their pet, but cost and time commitment with after care can be barriers. Our job is to provide them with solutions that make the best care possible—budget-wise, time-wise, and health-wise.

Root planing, local antimicrobial administration (LAA),

and laser periodontal surgery are often recommended for optimum care, but these simply may not be in the financial comfort range of some clients. This is where payment options can help to pay for the care they want for their pet or they can choose functional care.

Some pet owners may be unable or unwilling to provide needed follow-up care. In these cases, multiple extractions are usually necessary to create a pain-free, functional mouth. It may not be gold standard, but the pet will receive great basic care that supports quality of life.

Perhaps the most important thing to remember is that moving clients from fear to acceptance for their pet’s dental care is possible when we take the time to communicate the value and not just the cost.

Veterinary Fears

1. Oral Surgery

While the goal in veterinary dentistry is to save teeth, it often becomes necessary to remove some or all of the teeth. Indications for extractions include fractured teeth, advanced periodontal disease, non-functional orthodontic disease, and chronic ulcerative conditions. Oral surgery fears include excessive bleeding, inability to remove the entire tooth, jaw separation, and dehiscence. Fortunately, these worries are easy to change into happy opportunities.

- Excessive bleeding can be mitigated through avoidance, realizing that in the maxilla the most troublesome area surrounds the infraorbital artery, which exits the infraorbital canal just above the maxillary third premolar. In the mandibles the area to avoid is the mandibular canal. When either of these are breached, bleeding occurs, which can be minimized by elevating the head with towels, applying a hemostatic agent (Vetigel®), and gauze pressure.

- Inability to remove the entire tooth through root separation can usually be prevented by examining intraoral radiographs before the procedure, large exposure, and gentle luxation with a sharpened luxating elevator.

- Jaw separation, occurring usually secondary to advanced periodontal disease, is rare. Consultation with a veterinary dentist is recommended.

- Dehiscence is also rare and, in most cases, should be left alone to self-heal.

2. Not enough time

This proven workflow can eliminate time fears.

A client calls to schedule a teeth-cleaning visit due to oral malodor. The client care coordinator shares that your practice provides more than teeth cleaning. The client will be scheduling an appointment for oral prevention, assessment, and treatment (Oral PAT). This is the time to be sure clients understand the value of complete oral care:

- There is a dental cause for their pet’s halitosis.

- This will be diagnosed during the initial oral examination, pre-anesthesia testing, as well as a tooth-by-tooth examination under general anesthesia.

- Recommended treatment for the cause will be discussed, and it can be performed during the same anesthesia, time permitting, or at a later time.

- The doctor will make plaque and tartar control suggestions the client can perform at home to support overall oral health.

Here’s a timeline example…

9 a.m. The owner brings their dog or cat into the exam room. Review the history and previous laboratory results, examine the pet, and focus on the oral cavity. Discuss owner willingness and ability to provide daily plaque control. Share the value of the services, then discuss fees for initial diagnostics and dental scaling and radiograph imaging before the client leaves the exam room. The client agrees in writing that they understand:

- Anesthesia will be performed, and they have been informed of the associated risks.

- There will be additional fees if extra care is needed to treat the cause of the malodor.

- Payment options are discussed openly.

Next, inform the client what to expect from the day and arranges a time (1 p.m.) to speak to the owner while the pet is still anesthetized after the cause of halitosis has been determined.

9:30 – 11 a.m. The staff acquire pre-anesthetic test results to share with the veterinarian and prepare the patient for anesthesia.

11:30 a.m. – 12:45 p.m. The patient is anesthetized, teeth are cleaned, intraoral radiographs are exposed and placed in

a template for the veterinarian to examine chairside. The veterinarian is handed a dental probe to conduct the tooth-by-tooth examination and treatment plan, dictating results to an assistant who creates the dental chart. The assistant tabulates additional fees and creates a report or takes cell phone images, which are emailed to the client.

1 p.m. Talk to the pet owner to review what was found and describe optimum treatment and why it is important for their pet. Fees for the additional care are discussed, along with payment options.

3 p.m. Therapy (e.g., extraction of multiple teeth and application of a locally applied antimicrobial to stop bleeding on probing points) is completed.

5:30 p.m. The client meets with the doctor to review the diagnostics and therapy. A follow-up appointment is set to evaluate healing and create a daily plaque prevention program tailored for the pet.

3. Proper Assistance, Equipment & Instruments

An assistant goes far to lessen the load on the veterinarian during dental treatment.

Proper instruments and equipment are also important:

Elevators: Because there are a variety of sizes of teeth, one needs a variety of sizes of dental elevators. Generally, select the elevator that best fits the contour of the tooth to be extracted. The Heidbrink and Miltex 76 are root tip picks useful in elevation and for extracting retained root tips. They also can be used to cut the gingival attachment off the tooth prior to displacement with dental elevators.

Extraction Forceps: Smaller extraction forceps have been designed for dog and cat teeth. They have more parallel jaws, increasing the surface contact and are much more effective than the human incisor forceps formerly used in veterinary dentistry.

Magnification & Lighting: One frustrating aspect of oral surgery is the limited access and poor visibility. These problems may be decreased using magnification (2.5-3 power) and head lamps.

Sterilization of Equipment: Since extraction is a surgical procedure and the instrument penetrates tissue sterile instruments should be used. While it is true that the tissue surrounding the tooth is already infected, it is inappropriate to add different species of bacteria to the infection. Chemical disinfectants may be effective, but they take time to work, and must be thoroughly washed off prior to use.

Hemostatic Agent: Vetigel® is used to syringe over a bleeding area. Within a minute the bleeding generally stops.

Flaps: Surgical extractions are performed by making releasing incisions on the mesiobuccal and distobuccal line angles between adjacent teeth. These releasing incisions are joined by an intrasulcular incision that follows the gingival margin. The periosteum and gingiva are elevated off the bone with a periosteal elevator, to create a full-thickness gingival flap. The buccal plate of bone over the tooth is removed with a water-cooled high-speed bur. The root is removed, and the flap is closed without tension over the alveolar socket.

Postop

Radiographs taken postoperatively allow the practitioner to verify that the entire tooth has been extracted. Radiographs create a permanent record of the procedure. The possible pain to the patient caused by the disease condition or the procedure creates the need for consideration of pain medication administered by injection of a local anesthetic, parenteral injection, and oral pain relief medication.

Complications

- Tooth roots may become separated during the extraction procedure, creating non-extracted root fragments. The preferred treatment in this situation is to create a buccal flap over the fragment for removal.

- Collateral damage to other oral or extra oral structures including perforation and orbital contusion of the eye with sharp dental instruments.

Using proper instrumentation and extraction technique makes the extraction simpler, safer, and easier on the patient and practitioner. Multirooted teeth should always be sectioned prior to extraction to prevent the likely hood of fractured root segments. Difficult extractions can be accomplished by gingival flap surgery to facilitate atraumatic elevation of the root in a buccal direction. Pre- and postoperative radiographs and pain control help document what has been done and provide the patient with a relatively painless procedure.

Pet Fears

Let’s not leave out the patient, who is our most important consideration. Fear Free practices such as use of nonslip surfaces and techniques such as considerate approach and touch gradient contribute to the success of dental procedures.

Creating a Fear Free dental practice is achievable. I am always happy to help. Please email any questions (dentalvet@aol.com) or call on my cell 954-465-4200.

References

- DeBowes LJ. Simple and surgical exodontia.Vet Clin Small Anim 2005; 35:963–984.

- Gunew M, Marshall R, Lui M, Astley C. Fatal venous air embolism in a cat undergoing dental extractions.J Small Anim Pract2008; 49, 601–604.

- Holmstrom SE, Frost, P, Eisner ER. Exodontics. In:Veterinary Dental Techniques for the Small Animal Practitioner. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004, pp. 291–338.

- Kapatkin AS, Manfra Marretta S, Schloss AJ. Problems associated with basic oral surgical techniques. In:Problems in Veterinary Medicine. Dentistry. Manfra Marretta S ed., 1990; 2: 85–109.

- Reiter AM, Brady CA, Harvey CE. Local and systemic complications in a cat after poorly performed dental extractions.J Vet Dent 2004;21: 215–221.

- Reiter AM. Dental surgical procedures. In:BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Dentistry. Eds. C. Tutt, J. Deeprose, D. Crossley. BSAVA, Gloucester (UK), 2007, pp. 178– 195.

- Scheels JL, Howard PE. Principles of dental extraction.Sem Vet Med Surg 1993; 8:146–154.

- Smith MM, Smith EM, La Croix N,et al. Orbital penetration associated with tooth extraction. J Vet Dent 2003;20:8–17.

- Van Foreest A: Exodontia (tooth extraction in dogs).EJCAP 1993; 3:35–42.

- Verstraete FJM. Exodontics. In:Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2003; 2696–2709.

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.

Dr. Jan Bellows received his undergraduate training at the University of Florida and Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine from Auburn University in 1975. After completing a small animal internship at The Animal Medical Center in New York City, he returned to south Florida where he still practices companion animal medicine surgery and dentistry at ALL PETS DENTAL, in Weston Florida. He is certified by the Board of Veterinary Practitioners (canine and feline) since 1986 and American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) since 1990 He was president of the AVDC from 2012-2014 and is currently president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry. Dr. Bellows’ veterinary dentistry accomplishments include authoring five dental texts – The Practice of Veterinary Dentistry …. A team effort (1999), Small Animal Dental Equipment, Materials, and Techniques (2005, second edition 2019) and Feline Dentistry (2010, second edition 2022). He is a frequent contributor to DVM Newsmagazine and a charter consultant of Veterinary Information Network’s (VIN) dental board since 1993. He was also chosen as one of the dental experts to formulate AAHA’s Small Animal Dental Guidelines published in 2005 and updated in 2013 and 2019.

Want to learn more about Fear Free? Sign up for our newsletter to stay in the loop on upcoming events, specials, courses, and more by clicking here.

Brought to you by our friends at Zoetis. ©2022 Zoetis Services LLC. All rights reserved. NA-03139

Brought to you by our friends at Zoetis. ©2022 Zoetis Services LLC. All rights reserved. NA-03139

The pain exam starts with your customer service representative, maybe the most important person in the diagnostic team. They are going to hear the owner say things that an educated customer service representative might recognize as a sign of pain, such as not using the litter box, suddenly fighting with other animals in the house, or hiding in another room. The receptionist then has the ability to ask the owner to video the cat walking across the floor, using a step, or jumping to a favorite spot. The receptionist can also ask them to visit websites, for example

The pain exam starts with your customer service representative, maybe the most important person in the diagnostic team. They are going to hear the owner say things that an educated customer service representative might recognize as a sign of pain, such as not using the litter box, suddenly fighting with other animals in the house, or hiding in another room. The receptionist then has the ability to ask the owner to video the cat walking across the floor, using a step, or jumping to a favorite spot. The receptionist can also ask them to visit websites, for example

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.