Blog Archives

Rapid IM Sedation on a Feline

Performing injections can be a FAS inducing event for you and them. Debbie Martin, LVT, CPDT-KA, KPA CTP, VTS (Behavior) and Lisa Radosta DVM, DACVB show you how you can combine touch gradient, treats, and other Fear Free techniques to administer Sub-Q fluids in a Fear Free way.

“]

Getting a Cat on the Scale

Even the best feline patients can have trouble getting onto a scale let alone those with any level of FAS. Mikkel Becker CBCC-KA, CDBC, KPA CTP, CPDT-KA, shows how you can use Fear Free Techniques to get an accurate and Fear Free body weight measurement from your feline patients.

You must be a Fear Free member to access this content.

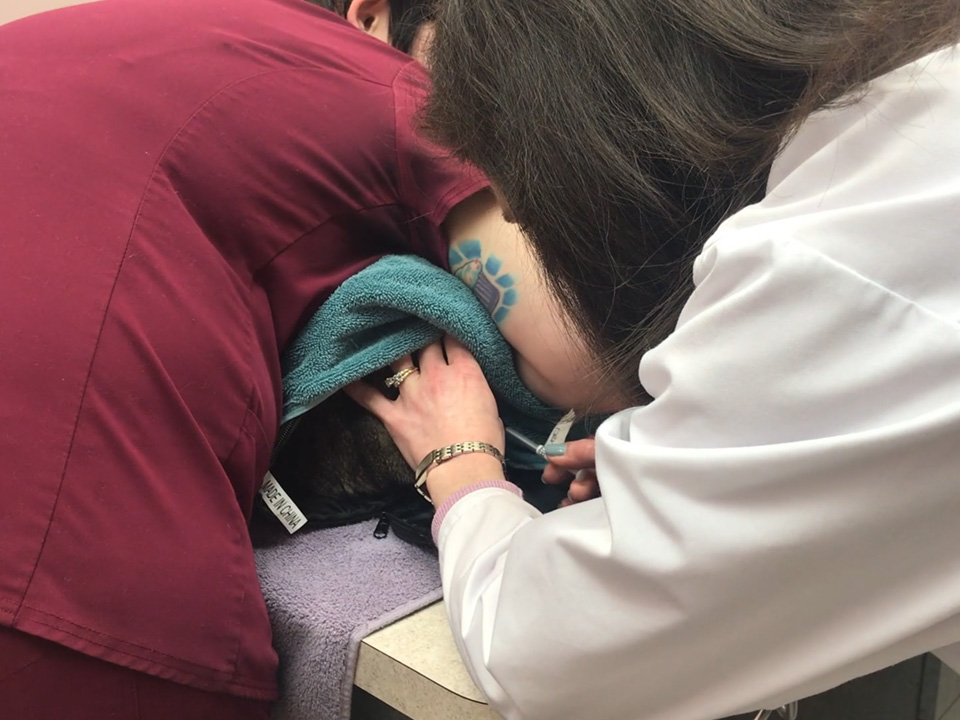

Feline Vaccination While Coaching the Owner

Vaccinations are something you do every day which makes the procedure an excellent way to practice proper Fear Free techniques. Debbie Martin, LVT, CPDT-KA, KPA CTP, VTS (Behavior) and Lisa Radosta DVM, DACVB show you how you can combine touch gradient, treats, and other Fear Free techniques to administer vaccinations in cats.

CEVA Practical Pheromone Use: The Road to a Calmer Pet Experience

Did you know the smells in an environment can affect the stress and anxiety levels of pets? Join Dr. Natalie Marks as she discusses the prevalence of fear, anxiety, and stress (FAS) in pets, how these can create unwanted behaviors, and methods to alleviate this stress for a calmer experience. FAS leads to a stressful experience in the clinic, grooming, or boarding and daycare environments, as well as in a pet and pet parent’s day-to-day lives. Pheromones are a successful tool to help alleviate stress and anxiety in pets. By combining the use of pheromones with the calm clinic approach, you can help create a calmer experience for pets and pet parents.

Brought to you by our friends at Ceva.

Based on that conversation the company started making “fearful cat” signs, but it got me thinking about the language of Fear Free and the terms I routinely hear vet professionals use for pets exhibiting FAS (fear, anxiety, and stress): “fractious,” “angry,” “spicy,” “CAUTION!!!”, and of course, a variety of R-rated terms used only in the treatment area. And I totally get it. No one wants to get bitten, scratched, snapped at, or injured, and it seems like these terms will keep us safer when approaching stressed patients. So why could this language be problematic?

Well, I’ve noticed that when there’s a patient alert such as “fractious” for a cat, people tend to approach the pet in an adversarial way. They put on their cat gloves, take a deep breath, and go into the exam room ready to do battle with their patient, which usually includes scruffing the cat to immobilize them. Unfortunately, this approach often has the opposite desired effect. Cat gloves can cause fear in patients, and scruffing is painful and takes away the cat’s sense of control. The “fractious” cat’s FAS levels then escalate, which increases the chances of getting injured.

Changing our language so that it describes and advocates for the emotional health of the patient can keep us safer. Instead of “fractious,” what about, “Fearful, keep in carrier until doctor is ready, prefers hiding under towel for exam and vax”? It’s rare to see these types of patient alerts, yet they take only a few seconds to update in a medical record.

Terms like “fractious,” “angry,” and “&#%!@” also shut down the empathy we should strive to bring to our patients, both feline and canine, and joking that a pet is “spicy” trivializes their emotional experience. Instead, see how it feels when you use patient-focused language such as “fearful,” “anxious,” and “stressed.” Just as most of us felt at least one of these emotions during the pandemic (or even all three at the same time), most of your patients are feeling at least one of these emotions during their vet visit. In fact, many of these “spicy” patients are utterly terrified and completely justified in their emotions considering all of the scary things they experience at the vet. Using terms like “fearful” and “anxious” also contributes to a Fear Free culture and sets the tone for how we’d like fellow team members to approach their patients–with empathy, not as adversaries.

As Fear Free professionals, we have the tools to identify, prevent, and alleviate FAS. Modeling Fear Free language is another important step we can take to bring compassion to the patients in our care.

Resources

https://fearfreepets.com/helping-our-feline-friends-feel-fear-free-with-dr-tony-buffington/

https://serona.vet/collections/cage-tags-signs?page=1

This article was reviewed/edited by board-certified veterinary behaviorist Dr. Kenneth Martin and/or veterinary technician specialist in behavior Debbie Martin, LVT.

Julie Liu is a veterinarian and freelance writer based in Austin, Texas. In addition to advocating for Fear Free handling, she is passionate about felines and senior pet care. Learn more about Dr. Liu and her work at www.drjulieliu.com.

Want to learn more about Fear Free? Sign up for our newsletter to stay in the loop on upcoming events, specials, courses, and more by clicking here.

Improving the Emotional Experience via Science of the Senses: Smell

This program will focus on the olfactory experience of canine and feline patients during the veterinary visit and the important role that it plays in the pet’s emotional health and physical health when under veterinary care. Join Jacqui Neilson, DVM, DACVB as she discusses the importance of protection against respiratory pathogens using Fear Free vaccination strategies.