Fear Free Pet Sitter – Preferences and Pet Peeves Form

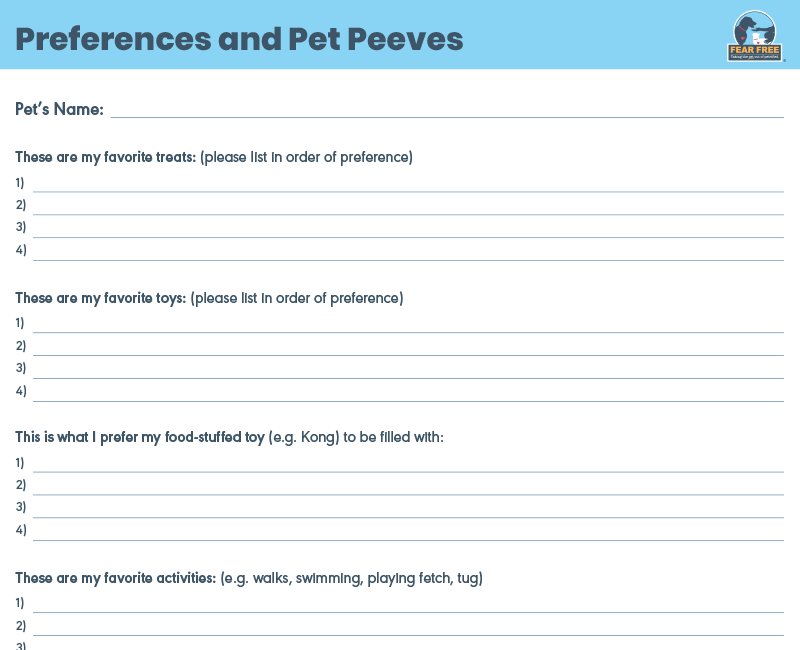

As pet sitters know, every animal is different! They each have their own favorite toys, treats, sleeping spots, and activities. Use this fillable handout to gather as much of your client’s pet’s preferences before you even step foot in the door. Not only will this make your sitting easier, but it will also help put the client’s mind at ease knowing that you’re taking every step you can to give their pet a Fear Free experience.

Boarding and Daycare – Preferences and Pet Peeves Form

A Fear Free experience during a pet’s boarding and daycare time is incredibly important. Use this fillable handout to gather as much of your client’s pet’s preferences before you even step foot in the door. Not only will this make your work easier, but it will also help put the client’s mind at ease knowing that you’re taking every step you can to give their pet a Fear Free experience.